This week Europe was treated to another show of the mutability of tech after Meta, the microtargeting ad empire formerly known as Facebook, announced it would be launching an ad-free subscription — with a starting price of €10 per month (on web) or €13pm (mobile).

As recently as mid 2019, visitors to Facebook’s landing page were greeted with a strap-line announcing: “Facebook is free and always will be.” But, by August 1, 2019 — doubtless anticipating regulatory bumps down the road — the claim had quietly vanished; in its place was a brief exhortation to new prospects that signing up is “quick and easy!”.

This wasn’t the first sign of a possible shift, though. Even earlier, back in April 2018 — as Facebook was embroiled in reputational fallout flowing from the Cambridge Analytica privacy and data scandal — its leadership explicitly said a version of its service that did not entail tracking and profiling the users would be a “paid product”. Well, five years on, here we are.

The slated pricing for the ad-free subscription puts the base cost of accessing Meta’s social networking services at roughly the same price as a Spotify Premium sub; Netflix’s standard offer; or an individual Apple Music subscription.

Does privacy sing and dance? Judging by those prices Meta wants you to think so.

And if you don’t want to add Meta to your monthly digital subscription toll the only free version of the service users in Europe will be offered will require they agree to being tracked and profiled by Meta’s ad targeting machinery. This is what the adtech giant means when it claims it’s switching its legal basis in Europe to “consent”.

You either consent to pay Meta money or ‘consent’ to pay with your privacy. The choice is yours!

Thing is, in the European Union — where Meta is rolling out the ad-free subscription option (alongside continued tracking and profiling for free!) — privacy is a fundamental right and citizens enjoy comprehensive legal protections for their information. Or they’re supposed to.

The EU’s data protection framework dates back decades but was substantially updated in May 2018 when the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) came into application — ushering in a legal regime with upsized teeth, including fines that can scale up to 4% of global annual turnover.

Overnight, on paper at least, the cost of ignoring Europe’s privacy rules scaled up considerably.

In practice, however, the GDPR’s application date kicked off a very slow burn — certainly where enforcement against Big Tech is concerned — which continues to this day thanks, in large part, to a regulatory structure that allows for giants to forum shop; shrinking their risk by setting up a main establishment in a more business friendly EU Member State, such as Ireland. As Meta has.

Despite the GDPR having a structure conducive to kicking privacy complaints into the long grass, the wiggle room for Meta to claim a legal basis in the EU for its tracking and profiling microtargeting ad business — which, of course, is anti-privacy by design; you can’t profile people for ad targeting if you can’t track what they’re doing — has been shrinking, as five+ years of privacy complaints, regulatory investigations and court rulings have reached some sort of show down in the case of Meta’s legal basis to run tracking ads.

Key moments include a $410 million fine and final decision in January which ended Meta’s ability to claim a contractual basis (aka performance of a contract) for ads processing. Then, this summer (July), a ruling by the EU’s top court removed Meta’s ability to claim a legitimate interest for tracking and profiling users — the basis it had switched to after regulators denied its ability to claim contractual necessity. Which leaves consent as the sole game in town (the other three of the GDPR’s six available legal bases for processing people’s data being irrelevant for Meta’s purpose of running a ‘relevant’ ads business).

Except it’s not, actually. Now the game Meta has embarked upon is to game consent itself.

Recent months have seen frustration at the bloc’s failure to rein in Meta’s flagrant privacy violations bubbling up into public view. An intervention by Norway’s data protection authority in the wake of the CJEU ruling, angry at Meta continuing to process people’s data without a valid legal basis, led earlier this week to the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), a steering body which plays a key role in settling GDPR enforcement disputes, issuing an EU-wide ban on Meta running targeted ads without obtaining people’s consent.

The EDPB’s “Urgent Binding Decision on processing of personal data for behavioural advertising by Meta” sounds like a really big deal. Until you remember Meta is in the process of switching to a different legal basis — and its version of consent is, intentionally, ‘Hobson’s choice’; either you agree to give up your privacy or you enrich Meta with your hard-earned cash. Either way, Meta wins. While Europeans desperate to protect their privacy must make themselves poorer in the process. Nice privacy if you can afford it!

The EDPB press release tacitly acknowledges it’s one step behind where the play has moved, taking note of Meta’s proposal to “rely on a consent based approach as legal basis, as it was reported on 30/10”. “The Irish DPC [Data Protection Commission] is currently evaluating this together with the Concerned Supervisory Authorities (CSAs),” it adds, signalling that the privacy enforcement football has been hoofed back into the long grass yet again. Plus ça change.

There is no guarantee the DPC will reject Meta’s consent paywall. Indeed, the authority didn’t have a problem with Meta claiming its users had signed up to a targeting advertising contract — until other CSAs and the EDPB forced its hand. So its track record here is poor. Anyone holding out hopes for Dublin to come with a swift smackdown of Meta’s consent gaming haven’t been paying attention to the last 5+ years of regulatory wrangling in Europe.

For European users of Facebook and Instagram where things stand now vis-a-vis their privacy rights is actually a step backwards compared to the recent past. Because claiming a legitimate interest to process people’s data for ads did at least require Meta to offer an opt-out — and, assuming you could find the right forms to fill in to file your request, Meta would (or said it would) stop ads-related processing. But no longer.

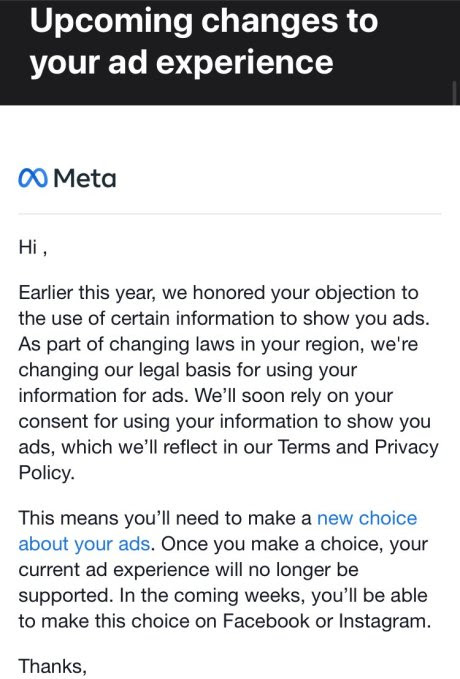

This week the adtech giant sent emails to users who had obtained this unprecedented opt-out from its tracking and profiling — instructing them the right they had so recently exercised will soon no longer exist. If they want to continue using Meta’s services it has a new form of forced consent to offer — one where they must pick between enriching Meta financially or ditching privacy… “We’ll soon rely on your consent for using your information to show you ads,” the email confidently ran. “Once you make a choice your current ad experience will no longer be supported.”

Image Credits: Natasha Lomas/TechCrunch

It goes without saying that fundamental rights are not supposed to work like this. An individual’s access to the legal protections wrapping their information should not be determined by their ability to pay a monthly subscription. But that’s the choice Meta has lined up as it seeks a fresh way to keep creeping on its users and clinging to a privacy-hostile business model that runs counter to the user agency Europe’s data protection laws intend.

Unlike stumping up for comparably priced digital subscriptions — like Spotify Premium, Netflix and Apple Music — Meta’s ad-free sub won’t tickle or delight your senses. The only visible sign of what you’re paying for will be slightly less content slurry in your social media feeds than usual; aka, none of those “relevant” ads that would otherwise have been programmatically slotted in to grab your attention.

Notably, the adtech giant hasn’t offered any justification for why it’s necessary to charge users so much to not be creeped on. Remember: Other forms of ad targeting are available. Types that don’t require processing individuals’ data — such as contextual targeting. Meta could have offered regional users a choice of accepting its “personalized” ads or ads that are targeted without tracking. Clearly, though, this company is not interested in getting out of the tracking business. Tracking is Meta’s business, period.

Meta’s ad-free subscription offer puts a financial cost on its access to people’s information — but it’s one which appears to inflate the value Meta derives from an individual’s data, making it more expensive than it should be for users to safeguard their privacy.

Doing a ‘back of an envelope’ pass on these figures: If we take Meta’s total monthly active users (3.74 billion, as of December 31, 2022), and assume every user is worth €120 a year in targeted ads to Meta (aka the annual cost of the ad-free subscription on web), then the company should be raking in around €448 billion annually. In fact Meta’s full year revenue for 2022 was the far lower figure of $116.61 billion (~€110 billion). Which implies its subscription offer overcharges individuals for protecting their privacy compared to the revenue Meta generates from continued access to their data. (Or, put another way, it’s a privacy rip off.)

This is important because the line in the July CJEU ruling which Meta has pointed to to justify its intent to charge a fee for the only version of its service that won’t demand users abandon their privacy stipulates that such a charge would have to be both “necessary” and “appropriate”.

Meta’s blog post includes just one line about how it calculated the level of pricing of the subscription — and only for the (more expensive) mobile sub — which it says “take[s] into account the fees that Apple and Google charge through respective purchasing policies”.

There is no information about why it has put such a high price for people to buy their privacy on web (where no App store or Google Play Store fees apply). So we can’t assess why such high pricing might be necessary and appropriate. Safe to say, Meta is keeping its arguments dry for the next round of regulatory and legal skirmishes.

The game of regulatory whack-a-mole it has perfected over the last five+ years in Europe is simple: Play as dirty as you like — even if it means clocking up some penalties along the way — but just be sure to reset the clock before the final whistle blows.

We put a range of questions to Meta regarding its plan to offer Europeans a choice of pay or be tracked but the company did not respond to repeated enquiries.

Nor have regulators been keen to talk about this topic — which risks falling between two (or even three) stools, with both data protection, child protection and antitrust components, implicating regulators such as Ireland’s DPC but also the European Commission itself, which oversees enforcement of the (newer) Digital Markets Act (DMA); an ex ante regulation that applies to gatekeepers like Meta (but is just getting started; and compliance for DMA gatekeepers doesn’t kick in until March 7, 2024).

A key DMA consideration for Meta is that the regulation stipulates gatekeepers’ core platform services must obtain users’ consent to process their information for advertising. It also specifies consent must be as easy to withhold as it is to affirm.

Is fishing out your credit card and paying a monthly fee as easy as tapping Meta’s ‘agree’ button and letting the adtech giant have its way with your privacy? Meta apparently thinks so — indeed, its blog post explicitly credits the DMA with inspiring its change to ‘consent’, along with referencing the CJEU ruling (and privacy regulators’ response to it).

It remains to be seen whether the Commission will agree with Meta’s interpretation of equivalent ease. The EU deflected questions about the subscription announcement at a press briefing earlier this week — saying Meta’s GDPR compliance is a matter for the DPC. (While the DPC deflected TechCrunch’s questions — suggesting we ask Meta — which… just ignored our questions. So it’s the full regulatory roundabout on this one!) So, most likely, we’ll have to wait to next year to see whether Brussels is going to call out Meta’s consent game or roll right on over.

There is one more interesting potential pinch-point ahead for Meta in the shorter term, if it goes ahead with its Hobson’s consent choice as planned, as it’s not clear how it will prevent children’s data from being processed for ads.

The Digital Services Act (DSA), another new EU regulation, which applies to Facebook and Instagram after the Commission’s designation of so-called very large online platforms (VLOPs) in April, includes a requirement that platforms do not process minors’ data for ad targeting.

The deadline for compliance with the DSA kicked in for VLOPs at the end of August. And, as with the DMA, the Commission is responsible for enforcement of Meta’s compliance. So it will also be up to Brussels to figure out if Meta is straying off the tracks on kids’ data.

The (ad-free) subscription version of Meta’s products will only be available to 18 year-olds+, so minors won’t be able to subscribe to the version that doesn’t have tracking ads. But, per Politico, Meta has said it will temporarily stop displaying all ads to minors in the region as soon as November 6 — owing to “legal uncertainty”, as it put it. However it’s unclear how Meta will confirm which users are minors in order to determine who gets served the (free) ad-free version of its services and who gets forced to see ads (or else pay). (Again, we asked Meta how it will identify minors to ensure it doesn’t illegally process their data but we didn’t get a response.)

Add to that, what’s to stop (adult) users who don’t want to pay Meta nor give up their privacy from signing up for new accounts that creatively shave a few decades off their age? It’s never been easier to fake an identity online. And Meta has never been good at purging fake accounts. So the possibility of some people figuring out a way to game Meta’s systems to avoid having to pay for its ad-free services looks real.

Or — an even wilder possibility! — Meta could roll out strong age verification across all its services, forcing users to confirm they are old enough to have to pay to protect their privacy. Albeit enforced age verification might be too controversial a step even for Meta (it has previously written about the complexity of understanding people’s age online at length, but in the context of trying to stop underage users from signing up for its services; so it would be ironic indeed if it ends up having to reverse its applications of age assurance tech to try to spot privacy-loving adults from masquerading as freeloading ad-free teens).

The DSA ban on processing minors’ data for tracking ads does come with a caveat — stating it applies to VLOPs “when they are aware with reasonable certainty that the recipient of the service is a minor”. So the fight here is going to hinge on the phrase “reasonable certainty”.

Meta’s lawyers will surely find plenty of self-serving descriptions for what’s reasonably certain where age assurance is concerned when it comes to the adtech giant failing to identify minors and serving them with tracking ads (oops!). But it will be up to the Commission, not the Irish DPC, to play referee this time. And that is new.

The EU has previously warned Big Tech against using “legal tricks” to evade the responsibility to deploy privacy by design. Now Brussels-based regulators are arriving at this long-running rights fight empowered to slap down infringements and ensure companies like Meta actually take kids’ privacy seriously.

Will the Commission step up to the plate and hit a home run or will Meta’s curve balls knock the EU’s shiny new rules flat? Long time privacy watchers in Europe will have a sinking feeling they’ve seen this game before — and their sense is it never really ends.

That Meta can execute such obvious dodges of data protection in Europe should be an embarrassment in a region that prides itself on being a rule-maker not a rule taker, as the Brussels lawmakers like to say. The DMA was supposed to be a game-changing reset to unchecked platform power; the DSA an ambitious playbook for driving accountability on those “move fast and break things” tech giants. Both regulations were also structured with the Commission taking a central oversight role of Big Tech’s compliance to, explicitly, avoid the pitfalls of patchy GDPR enforcement.

But with the ink still drying on the bloc’s updated digital rulebook it’s Meta projecting extreme confidence; as if there’s no battle to speak of.